US Pensions Looking North For Inspiration?

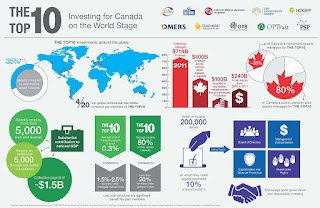

When it comes to at least one type of investing, U.S. pension funds should take a (maple) leaf out of their Canadian counterparts' playbook.

Despite being among the largest private equity investors, U.S. pension funds such as the California Public Employees' Retirement System and the California State Teachers' Retirement System have been slow to transition from a hands-off approach to one that involves actively participating in select deals, a feature known in the industry as direct investing.

A More Direct Approach

The benefits of direct investing are lower (or sometimes no) fees and the potential to enhance returns, and that makes it an attractive proposition. But so far, U.S. pension funds have been pretty content as passive investors for the most part, writing checks in exchange for indirect ownership of a roster of companies but without outsize exposure to any (click on image).

State of the StatesThis article basically talks about how Canada's large pensions leverage off their relationships with private equity general partners to co-invest alongside them on bigger deals.

State pension funds are comfortable writing checks to private equity firms but could bolster their returns by investing directly in some of those firms' deals (click on image).

Not so Canadian funds. A quick glance at the list of the private equity investors -- commonly referred to as limited partners -- that have been either participating in deals alongside funds managed by firms such as KKR & Co. or doing deals on their own since 2006 shows that these funds have had a resounding head start over those in the U.S.

Notably Absent

Large U.S. pension funds are nowhere to be seen among private equity fund investors that participate directly in deals, a strategy used to amplify their returns (click on image).

Canadian funds' willingness to pursue direct investing is driven in part by tax considerations: they can avoid most U.S. levies thanks to a tax treaty between the two North American nations, while they are exempt from taxes in their own homeland. But U.S. pensions would still benefit from better returns, so it's curious that they haven't been more active in this area.

There's plenty of opportunity for direct investing. Private equity firms are generally willing to let their most sophisticated investors bet on specific deals in order to solidify the relationship (which can hasten the raising of future funds). It also gives them access to additional capital.

Rattling the Can

Private equity firms recognize that offering fund investors the right to participate directly in their deals bolsters their general fundraising efforts (click on image),

The latter point has been a crucial ingredient that has enabled larger transactions and filled the gap caused by the death of the so-called "club" deals (those involving a team of private equity firms) since the crisis.

Seal the Deal

U.S. private equity deals which are partly funded by direct investments from so-called limited partners reached their highest combined total since 2007 (click on image).

There are some added complications. Because some of the deals involve heated auction processes, limited partners must do their own diligence and deliver a verdict fairly quickly. That could prove tricky for U.S. pension funds, which would need to hire a handful of qualified executives and may find it tough to match the compensation offered elsewhere in the industry. Still, the potential for greater investment gains may make it worth the effort -- even for funds like Calpers that are reportedly considering lowering their overall return targets.

With 2017 around the corner, one of the resolutions of chief investment officers at U.S. pension funds should be to evolve their approach to private equity investing. They've got retired teachers, public servants and other beneficiaries to think about.

It even cites one recent example in the footnotes where the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, or CDPQ, in September announced a $500 million investment in Sedgwick Claims Management Services Inc., joining existing shareholders KKR and Stone Point Capital LLC.

Let me cut to the chase and explain all this. An equity co-investment (or co-investment) is a minority investment, made directly into an operating company, alongside a financial sponsor or other private equity investor, in a leveraged buyout, recapitalization or growth capital transaction.

Unlike infrastructure where they invest almost exclusively directly, in private equity, Canada's top pensions invest in funds and co-invest alongside them to lower fees (typically pay no fees on large co-investments which they get access to once invested in funds where they do pay fees). In order to do this properly, they need to hire qualified people who can analyze a co-investment quickly and have minimum turnaround time.

Unlike US pensions, Canada's large pensions are able to attract, hire and retain very qualified candidates for positions that require a special skill set because they got the governance and compensation right. This is why they engage in a lot more co-investments than US pension funds which focus exclusively on fund investments, paying comparatively more in fees.

[Note: You can read an older (November 2015) Prequin Special Report on the Outlook For Private Equity Co-Investments here.]

On top of this, some of Canada's large pensions are increasingly going direct in private equity, foregoing any fees whatsoever to PE funds. The article above talks about Ontario Teachers. In a recent comment of mine looking at whether size matters for PE fund performance, I brought up what OMERS is doing:

In Canada, there is a big push by pensions to go direct in private equity, foregoing funds altogether. Dasha Afanasieva of Reuters reports, Canada’s OMERS private equity arm makes first European sale:When it comes to private equity, Mark Wiseman once uttered this to me in a private meeting: "Unlike infrastructure where we invest directly, in private equity it will always be a mixture of fund investments and co-investments." When I asked him why, he bluntly stated: "Because I can't afford to hire David Bonderman. If I could afford to, I would, but I can't."

Ontario’s municipal workers pension fund has sold a majority stake in marine-services company V.Group to buyout firm Advent International in the first sale by the Canadian fund’s private equity arm in Europe.Now, a couple of comments. While I welcome OPE's success in going direct, OMERS still needs to invest in private equity funds. And some of Canada's largest pensions, like CPPIB, will never go direct in private equity because they don't feel like they can compete with top funds in this space (they will invest and co-invest with top PE funds but never go purely direct on their own).

Pension funds and other institutional investors are a growing force in direct private investment as they seek to bypass investing in traditional buyout funds and boost returns against a backdrop of low global interest rates.

As part of the shift to more direct investment, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) set up a private equity team (OPE) and now has about $10-billion invested.

It started a London operation in 2009 and two years later it bought V.Group, which manages more than 1,000 vessels and employs more than 3,000 people, from Exponent Private Equity for an enterprise value of $520-million (U.S.).

Mark Redman, global head of private equity at OMERS Private Markets, said the V.Group sale was its fourth successful exit worldwide this year and vindicated the fund’s strategy. He said no more private equity sales were in the works for now.

“I am delighted that we have demonstrated ultimate proof of concept with this exit and am confident the global team shall continue to generate the long-term, stable returns necessary to meet the OMERS pension promise,” he said.

OMERS, which has about $80-billion (Canadian) of assets under management, still allocates some $2-billion Canadian dollars through private equity funds, but OPE expects this to decline further as it focuses more on direct investments.

OPE declined to disclose how much Advent paid for 51 per cent of V.Group. OPE will remain a minority investor.

OPE targets investments in companies with enterprise values of $200-million to $1.5-billion with a geographical focus is on Canada, the United States and Europe, with a particular emphasis on Britain.

As pension funds increasingly focus on direct private investments, traditional private equity houses are in turn setting up funds which hold onto companies for longer and target potentially lower returns.

Bankers say this broad trend in the private equity industry has led to higher valuations as the fundraising pool has grown bigger than ever.

Advent has a $13-billion (U.S.) fund for equity investments outside Latin America of between $100-million and $1-billion.

The sale announced on Monday followed bolt on acquisitions of Bibby Ship Management and Selandia Ship Management Group by V.Group.

Goldman Sachs acted as financial advisers to the shipping services company; Weil acted as legal counsel and EY as financial diligence advisers.

[Note: It might help if OPE reports the IRR of their direct operations, net of all expenses relative to the IRR of their fund investments, net of all fees so their stakeholders can understand the pros and cons of going direct in private equity. Here you need to look at a long period.]

There is a lot of misinformation when it comes to Canadian pensions 'going direct' in private equity. Yes, they have a much longer investment horizon than traditional funds which is a competitive advantage, but PE funds are adapting and going longer too and in the end, it will be very hard, if not impossible, for any Canadian pension to compete with top PE funds.

I am not saying there aren't qualified people doing wonderful work investing directly in PE at Canada's large pensions, but the fact is it will be hard for them to match the performance of top PE funds, even after fees and expenses are taken into account.

Who knows, maybe OPE will prove me wrong, but this is a tough environment for private equity and I'm not sure going direct in this asset class is a wise long-term strategy (unlike infrastructure, where most of Canada's large pensions are investing directly).

Keep in mind these are treacherous times for private equity and investors are increasingly scrutinizing any misalignment of interests, but when it comes to the king deal makers, there is no way Canada's top ten pensions are going to compete with the Blackstones, Carlyles and KKRs of this world who will get the first phone call when a nice juicy private deal becomes available.

Again, this is not to say that Canada's large pensions don't have experienced and very qualified private equity professionals working for them but let's be honest, Jane Rowe of Ontario Teachers won't get a call before Steve Schwarzman of Blackstone on a major deal (it just won't happen).

Still, despite this, Canada's large pensions are engaging in more direct private equity deals, sourcing them on their own, and using their competitive advantages (like much longer investment horizon) to make money on these direct deals. They don't always turn out right but when they do, they give even the big PE funds a run for their money.

And yes, US pensions need to do a lot more co-investments to lower fees but to do this properly, they need to hire qualified PE professionals and their compensation system doesn't allow them to do so.

Below, Julie Riewe, Co-Chief of the Asset Management Unit in the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Enforcement Division, sits down with Bloomberg BNA’s Rob Tricchinelli to talk SEC priorities in the private equity industry. You can watch this interview here.

Also, CNBC's David Faber speaks with Scott Sperling, Thomas H. Lee Partners co-president, at the No Labels conference about how President-elect Donald Trump's policies could affect private equity and jobs.

Lastly, regulation has been a "drag on the economy" and the "system needs to be debugged," Blackstone's Stephen Schwarzman recently said on CNBC's "Closing Bell."

Like I stated in my last comment on Ray Dalio's Back to the Future, inequality will skyrocket under a Trump administration and private equity and hedge fund kingpins will profit the most as they look to decrease regulations and increase their profits.

Comments

Post a Comment